Torment: Tides of Numenera Review

When Torment: Tides of Numenera first hit Kickstarter in early 2013, it set records for being the highest funded video game on the crowdfunding service and got plenty of attention, but it didn't even register on my personal radar. I hadn't played its godfather Planescape: Torment and I wasn't well versed in isometric computer-style rpgs at all. Fast forward a few years and the industry revitalization of the genre along with my newfound similar experiences with titles such as Divinity: Original Sin, Tyranny, and Pillars of Eternity had put me and Torment: Tides of Numenera on a collision course. All of a sudden I found myself eagerly anticipating the spiritual successor to a cult classic I had never even played. The more I read, the more I began to realize how different and weird Torment was shaping up to be.

I wasn't disappointed. It's a weird game. And all the better for it.

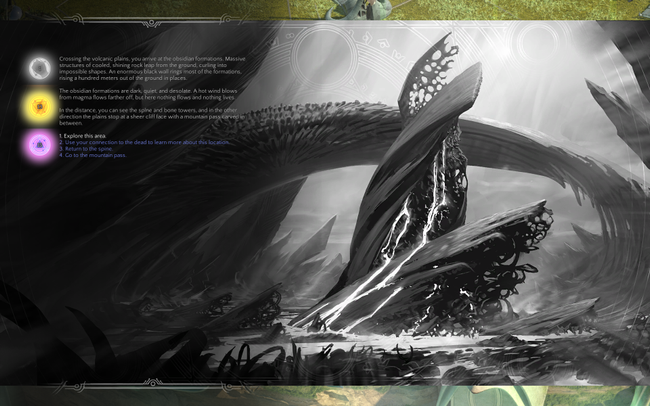

Torment: Tides of Numenera (for efficiency, Numenera), takes place a billion years in the future of the current world. Seeing how human life and human like ancestors in reality have at most only been around for (only) 6 million years, it's not surprising that the world in Numenera is as divorced from reality as any other fantasy setting out there. In this world (called the "Ninth World"), you play as a castoff character of a person known as the Changing God: a mysterious nigh-immortal character who has found a way to cheat death by transplanting his soul and memories from body to body. The manner in which he does this is never explicitly explained, but fits with the core of the game's theme that the technology has advanced to a point where it is indistinguishable from magic.

As the Changing God moves from body to body, improving the process each time, he leaves his castoffs with imposter memories but also with unique consciousnesses. In this way, the newer castoffs have more perfect bodies, higher level abilities, but are the youngest and least experienced of the family. As the Last Castoff, this is a perfect setting for creating a character of high importance but with an undetermined set of personalities traits and motivations and no prior history: it's a pretty creative and functionally brilliant setting for a role playing game.

At its core, Numenera has all the mechanics you would expect for any similar rpg: you undergo a short character creation section, you find your player character in an unfamiliar place you know nothing about, you come across companion characters with their own stories, goals, and abilities. You'll manage inventories, solve quests, engage in combat encounters, and all the like. In this way, there is not one overarching mechanic that separates Numenera from its contemporaries. Instead, there are numerous small ways that this game approaches familiar trappings of fantasy rpgs and utilizes them in weird ways. The more I played, the more I concluded that weird is good.

The gameplay starts out in a familiar fashion: you'll choose between a male or female character and pick a Type.

- Glaive: The combat specialists of Numenera. Generally expected to specialize in Might and/or Speed, and will be adept at intimidating characters to do what they want.

- Jack: The skill class of the game. They specialize in several abilities and would generally benefit from an even spread among the stat pools.

- Nano: The "mage" of the game. They will specialize in the Intellect stat pool and often use persuasion to avoid conflicts. I played through the game as a Nano.

You'll get a chance to select from a pool of talents specific to your class. They can be passive inherent abilities or active ones to use in combat.

The three main stat pools are Might, Speed, and Intellect, and these serve as the basis for skill checks both inside and outside of combat. These are both treated like stats but also as literal pools: a resource that can be exhausted and must be replenished by using consumable items or resting. Exhausting any of these pools will greatly limit your options in conversation and the options you have in battle, until the next time you're able to rest.

Next you'll pick a Descriptor: this is a list of prefixes to your class (ie, "Clever") that will grant you a small passive buff for one skill or combat ability. For all of these selections, the game will give you a starting point based on your answers to some questions, but you'll be able to deliberately select what you want from a menu before finalizing your decision.

Lastly, a short ways into the game you'll select a Focus.

- Brandishes a Silver Tongue - increases chances your ability to persuade people either through deception or intimidation.

- Masters Defense - which increases your defense in combat.

- Breathes Shadow - allows you to perform surprise attacks in combat in specific situations.

So all together, your descriptor, type, and focus will define the base parameters of your character. My character was a "Clever Nano that Brandishes a Silver Tongue."

Most of the core gameplay of Numenera involves piecing together the foreign memories in your head, which belong to both the player character as well as the Changing God. You'll take on quests with characters that know various levels of detail about your situation: some will have met many castoffs and others will not notice or care. You'll find objects for people, solve problems, and be forced to pick sides in conflicts. In some way these are typical sorts of quests that at a surface level don't distinguish themselves much from other games. However, Numenera's highly unique setting will give each of these types of interactions a level of flavor that easily makes many of them more memorable and compelling: for instance, the ability to use items called Merecasters to enter the memory of another person and change their reality is a recurring theme that many parts of the game utilize. The Last Castoff has the ability to effectively roleplay as another character inside that other character's memory, learn what that character learned, and then take an action to change how that memory played out, maybe even changing who lived and died. I don't even know what to compare that to from another game or otherwise. What?

That's the most extreme example, but the gameplay in Numenera often leans against the game's one-of-a-kind setting in its quest writing: you'll house characters (or spirits of characters) in the Castoff's Labyrinth, a location inside your mind to help solve their problems. You'll have to learn what to feed to fleshy maws inside of a giant trans-dimensional organism (which doubles as a city by the way), that eat anything ranging from a person's legs, to their memories, to the emotion of guilt itself to open portals to other dimensions. But you'll also fetch missing books and break people out of a jail. There's a lot of breadth and variety.

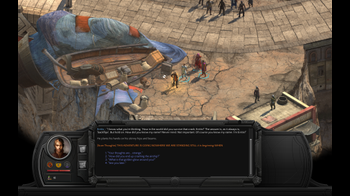

What's a little less engaging is the combat of Numenera. Unsurprisingly, many of the quests in the game will undoubtedly place your team against some sort of enemy monster or faction. Appropriately, the games calls these "Crises" instead of of something like "Battles", because even if you are unable to prevent a Crisis from occurring, you can often avoid any real conflict by talking out the problem from within the Crisis itself, using the environment to end the encounter in a nonviolent way such as trapping the enemy, or simply by running away. The main difference here is that you'll have to play though using the turn-based ruleset while trying to end the Crisis non-violently. This can range from trying to distract a neutral character while trying to sneak around behind his back before too many turns pass and he notices, or trying to evacuate npcs from a location while not directly engaging in the oncoming attackers to give some examples. While it's often satisfactory to have non-violent runs in other games ranging from rpgs that allow for pacifist options or stealth games where avoiding conflict represents a sense of mastery: in Numenera I found that while this held true in some respects, what also held true is that fighting in this game is simply not very fun.

Battles drag on and the player often finds themselves outnumbered by enemy (or neutral) units. What this means is that your party of at most 4 characters will often have to wait through the turns of 10-15 other units before you have a chance to have any input again. Combat animations are stiff and boring and usually are more time consuming (again, due to the amount of waiting) than they are challenging. This seems like a good place to mention that Numenera does not have any difficulty settings. There's some satisfaction in being able to specialize your party to be able to adeptly handle the few combat scenarios that come your way: having one character with the ability to soak up damage while others are able to finish off enemy units and finding good combat combinations is still fairly rewarding. However, I found myself wanting to avoid combat more than anything. Luckily, Nano type characters seem to come with the most appropriate toolset with this goal in mind.

Despite the lack of combat focus in Numenera, there are numerous opportunities to upgrade equipment at shops, designate specific Cyphers to certain characters, and specialize in specific combat skills or talents. It almost comes across as a little bit of a disconnect with the progression-heavy and combat-lite nature of the game. In 25 hours I ignored maybe a half dozen shops and only visited my equipment screen a handful of times. Perhaps Glaive type characters with a focus on solving every problem by reducing a few HP bars to zero would make more use of the game's overly numerous equipment and item shops, but anyone that gets deep into the quest experience of Numenera will find themselves discovering peaceful solutions to the many conflicts without really even trying. Nano-focused characters with high persuasion and/or deception ability with a similar disdain for finding an actual battle will fight maybe once every handful of hours.

One aspect of the game that allows avoiding combat in Numenera to result in a more interesting game is the quality of the writing. Very little of the narration is voiced, even for companion characters. There is no real artwork used outside of the Merecaster segments, and important NPCs are not even given character portraits. You have to read. Luckily, I found the level of writing high enough and useful enough to be worth diving headfirst into. Since the in-game isometric models are basic and merely functional, reading the descriptions for each character the Last Castoff comes into contact with allowed me to paint with my mind's eye a mental image of each character. Quests and story progression involving these characters would rely on the information learned in conversations with them, without waypoints or arrows or map markers to remind you where every important person is (though the quest log will suggest speaking to specific NPCs by name). Skipping conversations and then trying to select the best looking conversation option is probably doable, but far less fun.

Companion character writing is equally compelling. Companions have complex emotions and motivations and are not able to be boxed into specific tropes or archetypes, at least not very easily. One character is a selfish ex-soldier who has let down a number of people close to him but also struggles internally with personal demons lingering from having reluctantly pushed away an ex-lover in the past. Another is a freed slave with a unique set of viewpoints on the world, such as letting you know the importance of understanding the difference between a rock and a stone.

All in all, I came across 6 or 7 potential companion characters and it was an unusually hard decision to have to narrow it down to three later in the game. Learning more about the companions and fleshing out their stories is not always given a tangible gameplay reward either. Completing one character "quest" in a certain way will remove that character from being able to be used, and not in a way where it's written like an undesirable outcome. Being able to see the conclusion of these characters arcs is its own reward, not some unlocked in-game talent or ability handed out for being nice enough for long enough. The stories proceed naturally and doesn't tether itself to the notion that completing a quest must reward you with something.

Torment: Tides of Numenera stands out from its contemporaries due to the strength of its world and setting, which while different and weird, remains strongly cohesive. Numenera has an absolutely brilliant narrative setup for uncovering both the overall game world as well as the mysteries surrounding the player character. While its ability to match the cult classic status of Planescape: Torment has yet to be seen, the high quality writing, unique questlines, interesting characters, and plenty of bizarre moments make Tide of Numenera defintely worth making time for.