Zero Escape: Virtue's Last Reward Review

For the first time in nearly two years, I was locked in a death grip.

A certain game had grabbed hold of me like only one other before, and once again I was propelled head first into the world of numbers, persons and many doors. Of course, it wasn’t that peculiar DS game I was playing – no, in fact its follow-up is here – and a direct one at that.

That game is Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward and it’s not your every day sequel.

I guess you could say 9 Hours, 9 Persons, 9 Doors was only the tip of the iceberg. As the second entry in the Zero Escape series, VLR succeeds in being an even bigger adventure than its predecessor while managing to paint an even more captivating tale than the original.

VLR opens with main character Sigma – abducted on Christmas in the year 2028. Seemingly knocked out by some strange gas by a masked figure, our hero wakes up kidnapped in what can only be described as a mysterious, elevator-like room. Sigma, however, is not alone.

Trapped with him in his moment of terror is a young woman by the name of Phi. For some reason, she somehow knows Sigma’s name, but what else does she know? What is this place, and why were they both kidnapped? These questions don’t remain unanswered for long – appearing on the screen in that very room was a holographic, rabbit type creature who goes by the name of Zero III.

Zero III is supposedly in league with the one behind the pair’s kidnapping, and claims the two must play the “Nonary Game” in order to escape their predicament. The only catch is – they have 9 minutes to escape or the elevator they’re in will plummet to the bottom. Terrifying circumstances to be sure, but with enough willpower and deductive reasoning, Sigma and Phi make it out right before the time limit.

Upon their escape they discover they’re not in an elevator shaft, but in a massive warehouse. What’s more is they’re not alone. Sigma and Phi meet up with seven other strangers who just experienced the same trial. It’s only then that they discover through Zero III that they’ve all been gathered to take place in a life or death experiment.

Unlike its predecessor, there's no sinking ship, no bombs, and there’s no time limit. Despite that, the threat of death is still very real. Instead of the aforementioned, Sigma and crew will have to play a different sort of game – an Ambidex Game of trust and betrayal. Failure to cooperate in this game will lead to certain death by means of a slow injection via bracelets the nine gathered have been forced to wear.

With an assorted cast who all seem to have different motives, securing that trust isn’t going to be an easy task.

If that wasn’t enough for you, the adventure ahead is filled with many choices. Those familiar with the original 9 Hours, 9 Persons, 9 Doors will likely recognize the set up. VLR operates like your typical adventure game which is left to the player to make important decisions. After all, the lifeblood of VLR is centered on the decisions you make, and how they affect both Sigma and the characters around him. Numbered doors are now colored doors, and your ability to go through them is decided by the chromatic color scale.

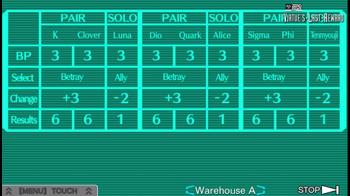

As with 999, each character has a bracelet with a number on it. Beginning with three, the goal is to achieve 9 or more bracelet points (or BP) in order to open the number 9 door to escape to freedom. Who you decide to pair up with and whatever door you decide to enter will ultimately decide your fate, so choose wisely. VLR has a total of 24 endings to discover, so you’ll be given the luxury to return to various points you’ve already seen in order to unlock the rest of the game’s many mysteries.

The gameplay of VLR is shuffled into two parts: novel and the escape. The novel part is exactly as it sounds – text and interactions between characters, but presented in a more visual sense. They don’t call them “visual novels” for nothing, after all. Contrary to popular belief, however, these things typically do have puzzles or mini-games in between their massive amounts of dialogue, and VLR is no different.

The escape portion of the game is fairly straight forward. Upon entering one of the various doors set within the facility, Sigma and two others selected from the remaining characters will have to work their way through puzzles and other hints laid throughout a multitude of rooms. Each room contains a safe that must be unlocked with a series of symbols; in order to get the password to that safe, you’ll have to interact with objects around you and determine where they all fit into the scheme of things. The L and R buttons allow you to cycle through different screens, and by use of the touch screen you can examine and even pick up objects to either investigate or combine with other items or keys.

While VLR lacks that sense of urgency that was evident in 999, it still succeeds in creating its own special brand of tension. The core mechanics of the game revolve around the choices made not only by what door you enter, but by what outcome you choose in the Ambidex Game.

Will you choose to ally? Or to betray? VLR is not just an extreme escape adventure, but one that tests the player’s faith in humanity. After each turn in a puzzle room, you’ll have to face the Ambidex Game (or AB Game.) Each group of three characters consists of one pair and one solo, and in the AB Game, the pair will face off against the other – both given the choice to either ally or betray one another. If both groups choose to ally, they will gain two points which will be totaled on their bracelets. If both choose to betray, they’ll gain nothing. If one side choses ally, while the other choses to betray, the group that betrays will gain three points instead of two, while the side that chose ally will be penalized by two points. As a result, those who pick betray have a greater chance of getting out faster, as long as their opponent happens to choose ally.

Much like anything, these choices aren’t easy. You’ll often find yourself wondering if your opponent’s promises to vote a certain way remain true, or if they’re simply lying through their teeth. It’s those tense moments that build up during every voting round that really do well in accomplishing both the tone and often terrifying outcomes as you progress through the story and revelations behind each character as they show their true selves. It's the classic prisoner's dilemma.

The idea of 24 endings may seem like a lot, but not all of them are pleasant. Only through trial and error will you find your way to the one true ending. VLR offers multi-branched paths which can be accessed through the main menu. After completing any given segment, you’re then allowed to “jump” back to the beginning of the scene any time you wish. Recycled dialogue can be skipped completely, and the ability to forgo puzzles you’ve already solved is also a plus. Replaying an entire path, however, is not necessary. You can pick up and start a new path at certain junctions where choices were previously made in order to progress faster. Each new path brings with it even more intricate revelations – some that you won’t even see coming.

Without spoiling too much – after all, the main allure of VLR is in fact its story – I’ll say that not every ending is conclusive. There are several which provide absolute moments of amazement, but it won’t be until the true end – which can’t be accessed until you complete all of the other endings – that all answers will be revealed. The intelligent story really comes full circle for those who played 999, so I can't stress enough the importance of having played it prior to starting VLR. If you haven't experienced the original, however, there's still much enjoyment to be had here. Just remember, it's called "Zero Escape: Volume 2" for a reason.

It’s through these multiple paths that your grip on reality (and your sleep patterns) will be tested. As it turns out, VLR is incredibly addicting – so much so that the sheer amount of choice and path exploration kept me hungering for more. VLR doesn’t just have one major mind-bending revelation, but several. It’s these moments that make it a bigger and better game than its predecessor in that you’re given much more time to grow emotionally attached to the characters, and by the end you’re left grasping for much more.

Perhaps the most striking quality of VLR outside of its original plot is the game’s English localization. Aksys Games have really gone above and beyond to bring entertaining dialogue to the stage. They’ve done well to bring a full set of emotions to the characters, and taking the translation to new heights by adding flair of their own. Laughter; anger; sadness – all of these things really impacted me while playing, and it’s something which would have likely been lessened had I simply played the Japanese version.

Options for English or Japanese dialogue are intact, but I implore you to check out the English dub. Nearly every single choice was a fantastic one and some even more so over their Japanese counterparts.

Shinji Hosoe returns once again to score VLR, and those familiar with his work in 999 will know exactly what to expect. While the OST in VLR is very similar, it remixes certain themes, and does well to play appropriate music when necessary in the game. The music is what I’d describe as very ambient; there are a few standout tracks, but the majority of them are there to set the mood.

Of course, Virtue’s Last Reward is far from a perfect game, although it comes quite close to it. The issues that arise during the 30+ hour adventure are minor and somewhat subjective. The most obvious one comes from the camera control during the escape room segments. Moving around can be very robotic at times as you’re not given free control, but confined from moving from one view to the next. As a result, positioning yourself can feel awkward, or having to cycle back to a certain part in the room can feel somewhat tedious.

My second complaint comes from some of the game’s puzzles. While the majority are arguably easier than 999’s, there were a couple that really left me frustrated by their lack of information given, and one straight up random puzzle that was ultimately unnecessarily irritating. That said, everything else was smooth sailing and if you really get stuck, you can just default to Easy mode to pick up some more hints along the way.

Lastly – and this is the subjective area – the game’s art style. The original game took a more 2D sprite approach in its design, with pseudo-3D backgrounds in between. With VLR, the 2D sprites have given way to 3D models to fit more in line with the game’s 3D environments. While glimpses of Kinu Nishimura’s beautiful illustrations still exist between the pages, the designs haven’t quite translated well to 3D modeling.

So while those are the issues, they certainly don’t take away much enjoyment out of the game. It’s quite the opposite really – you’ll be too engrossed in VLR’s narrative, often finding yourself dangerously attached to certain characters whether you like it or not. As I said, no game is truly perfect but VLR comes close – a feat in itself considering the ultimate simplicity of it all.

Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward may not be for everyone, but if you love well-written, intelligent stories, and a lengthy adventure that keeps you on the edge of your seat at every turn coupled with an outstanding localization – this game is for you.

Disclaimer: This review was based off final retail code of the English PlayStation Vita version of Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward provided by Aksys Games.