Star Trek: Voyager - Across the Unknown is a strategy gem that has uber-satisfying RPG chops

The Steam page for Star Trek: Voyager - Across the Unknown describes it as a Strategy game. This makes perfect sense, given how its core loop plays out. But after slipping into a low-key addiction that currently stands at some thirty hours long, I also think it’s fair to say that there’s plenty of role-playing DNA here that readers of this site will likely love.

Across the Unknown is a very cleverly-pitched tie-in to nineties TV staple Star Trek: Voyager, correctly recognizing the show’s unique pitch - a ship stranded tens of thousands of light years from friendly space on a potentially decades-long journey home - is the perfect framework for video game nonsense.

The result is a curious game. There’s spacefaring ship management and combat stuff that is reminiscent of FTL, which is for my money one of the greatest indie games of all time, and an obvious fit for Trek. But then the mechanical melting pot grows: side-on base building reminiscent of XCOM, a galaxy map that evokes Mass Effect 2 & 3’s resource hunting, and text-driven away mission adventures complete with D&D-esque rolls for skill checks. Finally, there’s visual novel style storytelling that’s heavy on the choice and consequence, which of course is very much our bag. Basically, it ticks the boxes.

Described in these terms, Across the Unknown isn’t exactly breaking new ground. It is a very competent expression of a bunch of stuff we’ve seen before, welded to a lovable and recognizable IP. But y’know, that’s fine - we don’t always need a reinvention of the wheel. Sometimes we just need something good, of quality and with heart - and this is very much that. I quickly fell in love with it.

The cleverest thing about it in a sense is how the TV show is used as a framework. The same characters and events pop up throughout the adventure in roughly the same order, but how exactly everything plays out can differ.

Maybe you disagree with a moral decision made by Captain Janeway in the show; you can now make a different one. The order in which you approach missions, the methods used during them, the layout of your ship or even your research priorities can result in you having different tools than they’d had in the show. Perhaps you can save a life that in the show’s canon storyline was beyond help. Or you could develop the ship to have such overwhelming weapon systems that what would’ve been impossible combat odds in the show becomes a viable brute-force path through the Delta Quadrant.

As the ship progresses on its journey, the repercussions of these decisions can snowball. By the halfway point, I had a ship that was equipped and crewed totally differently to the one in the show. Characters who had died, left, or been exiled had instead been rehabilitated into the crew as powerful heroes. The more my decisions compounded to differentiate, the more those differences allowed me to shear ever further from the path cut by the show’s narrative. Equally, this is a game with a ‘Canon’ achievement, granted for seeing credits roll with a ship and crew complement that matches the eventual outcome of the TV series.

All of this is supremely interesting in the context of somebody who knows and loves the original show, but I imagine it’ll also be just as potent for people who have never seen a shred of Voyager - or even Star Trek - in their lives. At its best, Star Trek is always a sort of moral play each episode, holding a mirror up to some aspect of modern society and examining it through the lens of a far-flung future.

Such moral quandaries are the perfect kinds of choices to put in front of players in a game like this. You will inevitably hover, unsure, over certain A/B decisions, with that slight pit in your stomach. Good. You’ll press it, and with a bassy sound the UI delivers the reminder: ‘YOUR CHOICE HAS CONSEQUENCES’. You might think about save scumming, but an unforgiving autosave and total absence of a manual save means you can’t. Even Better.

Alongside the big and impactful, you’ll also need to manage the granular. A crew mutiny is just as much a threat as being blown to bits. So too is simply running out of fuel or food. Fulfilling crew requests is important, then - as is the broader task of power management. If you keep all your systems running all the time, you’ll struggle to provide enough power and burn through all your fuel. If you’re cleverly turning systems you don’t need on and off as required, things become easier, though obviously the burden of that micromanagement is on you.

A great example of this is how it uses a lot more fuel to use Star Trek’s famed food-creating replicator technology - so a vital bit of resource management is knowing when to switch the replicators off in favour of ‘real’ food foraged from life-bearing planets. But proper food is also a limited resource - so a smart player will be flicking back and forth between the two as they traverse a sector in order to maximize the resources available. This sounds like busywork, and it is, but it’s satisfying to master.

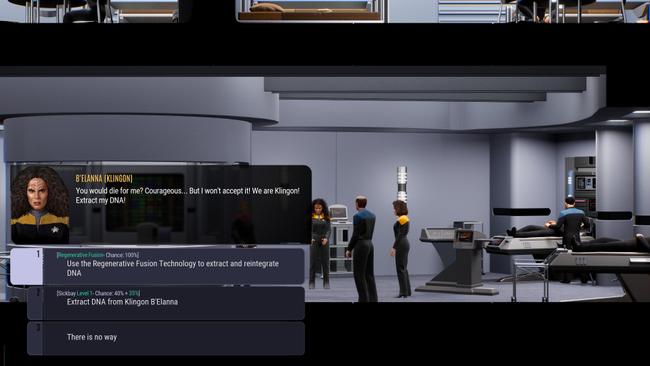

For away missions, your choice of heroes determines which actions are available mid-operation and how likely they are to work out. You’ll be carefully picking a gang of three to beam over to ships or down to planets on missions, and then even more gingerly choosing what actions they take in the hopes of breezing through the encounter with a bunch of critical successes - or at the very least, with no injuries or deaths. These missions, framed simply with text and still artwork, are nevertheless thrilling.

That’s the headline story of Across the Unknown, in a way. This is about as cheap and cheerful as licensed games come. You can tell this will have had a modest budget and a small team. You’ll get one piece of voice acting from a pair of the show’s stars per chapter of the narrative, for instance - everything else is text.

Some of the characters rather look like they’ve had a botched transporter trip when compared to their real-life counterparts, despite about 125 hours of reference material to check in the form of Voyager on telly. But I’m honestly fine with all that - it hardly matters when the rest of the game’s design is so sharp. These are small things in a game that is bursting with heart, and soul, and a real passion for its source material and the games that clearly inspired it. I love it.

It also, yes, clearly scratches the role-playing itch for me, just in the same way that XCOM did. Here is a game where your choices aren’t just dialogue, but instead shape the ship’s destiny. I think a strong case could even be made for reviewing Across the Unknown on this website - but instead we’ll settle for this hearty recommendation.