Stray Children Review

Moon: Remix RPG Adventure was my first game from now-defunct studio Love-de-Lic. The PS1 had a library filled with art games that all feel like “One-In-A-Million”s, yet Moon is still high up on that list for truly unique games. I loved my time visiting it a few years ago, but I was sad that none of the games from the many companies that splintered off from Love-de-Lic’s demise seemed to scratch the same itch for me. Onion Games, the latest iteration of the company, seems to agree.

Stray Children is — in many ways — a spiritual successor to Moon, but it’s not satisfied with solely being that. If Moon was a reflection of RPGs and adventure games in the '90s, Stray Children is a reflection on the last 30 years of video games as an art form. There’s something deeply introspective about how this game interrogates the history of games, and even Love-de-Liv’s impact on the medium.

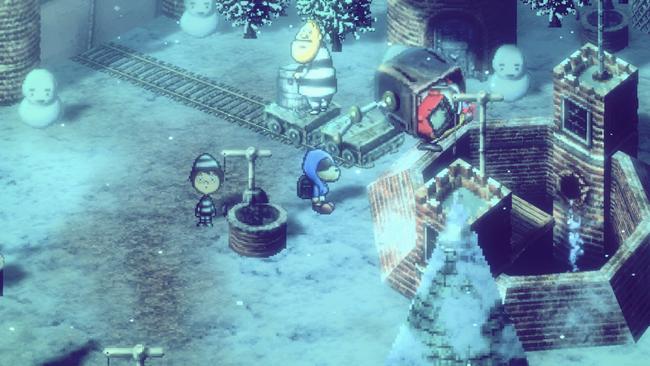

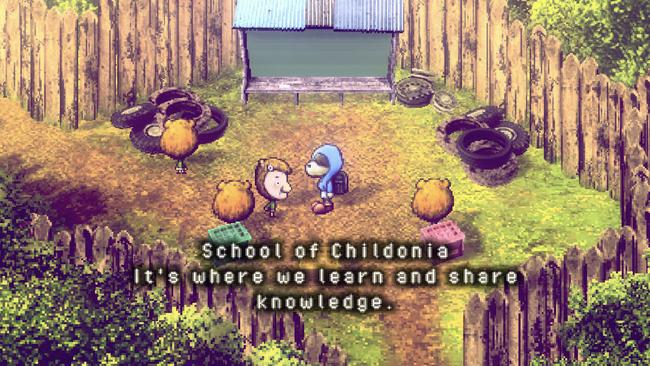

You play as another boy who falls into a video game cartridge, but this time, it is one made by your father, who has gone missing. As the world starts to crumble around you, you have to roam the land to reassemble the cartridge to make it home. To do this, you go from zone to zone, meeting the odd children residing in each area who fear the horrifying Olders. There’s something so simple about how Stray Children presents itself. You don’t even have a title screen, or even a detailed options menu. It truly commits to its retro aesthetic and asks you to focus on experiencing it over all else.

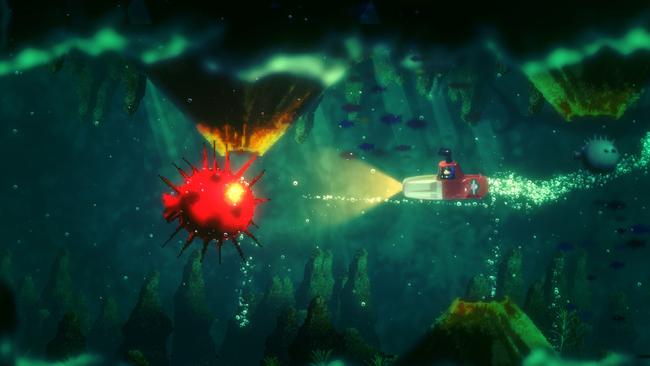

This aesthetic is truly unlike any I’ve ever seen. We’ve seen a lot of classic pixel style throwbacks to ’90s gaming, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen one look as good as Stray Children. I genuinely do not know how they pulled any of this off, combining 2D and 3D masterfully to create a game that feels like it could have existed on the PS1. There’s a large variety of backgrounds and maps to explore, all with gorgeous pixelated edges to create a cohesive style. Occasionally, it’ll bring in 3D assets, but they purposefully lack anti-aliasing to better match the 2D sprites.

While Moon was an anti-RPG, Stray Children is unabashedly inspired by the likes of Undertale. There are still light adventure game elements and plenty of puzzles to solve, but now you have turn-based battles with action commands. There’s gear in the game to increase damage, defense, and luck, and this will change how much damage you give and take in battles. You’ll go to attack and get combos by hitting the action prompts in a specific window. It’s simple, but it works. In the spirit of the company’s history, though, every battle in the game has the option to simply talk it out. This changes battles into logic puzzles.

That puzzle design is quite mean, but that kind of mean where you just know the people making it were giggling to themselves. My philosophy when it comes to friction like this? I’d much rather join in on the joke. Playing a pacifist in this game is (fittingly) an exercise in frustration. To beg for peace in the face of violence is never easy, and Stray Children truly makes you work to achieve this.

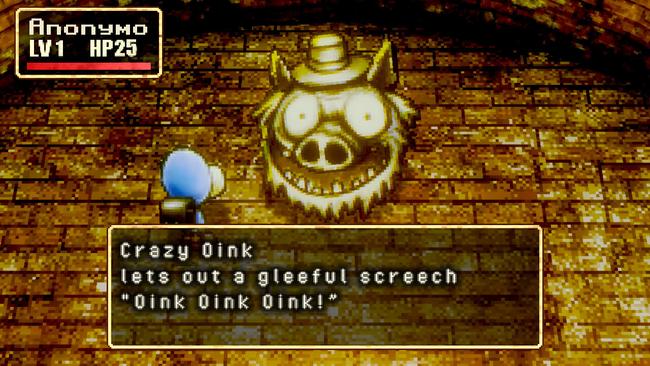

The Undertale inspirations mostly come from the bullet hell sections in battle during an enemy’s turn. During this phase, you’ll have the ability to freely walk around the arena, as unique projectiles for every enemy fly at you to dodge. Your little guy walks pretty slowly, but enemy attacks feel designed in such a way to always make you perceive them as faster than they are. I’m sure veteran bullet hell enjoyers might find this game on the easier side, but that is not who I am. I did, however, find these sections challenging but ultimately surmountable.

Morally, why one would choose to play in either different styles is kept secret, but have faith that the ultimate answer is very “Love-de-Lic”ian. I decided to fight all battles non-violently simply because I wanted to challenge myself, and while I had a much longer playtime, I think it was worth it. However, from a gameplay perspective, playing a pacifist is much more interesting since that’s where the most fun bullet hell sections are. Every Older has a puzzle around the right words to say, with a unique series of phrases you’ll have to say in a specific order to pacify them. A correct choice will have them show approval; an incorrect one will get them mad. Make all the correct choices, and then they’ll enter a final attack state before letting you click “Open Sesame” to free their soul.

The more you pick away at the walls of an Older’s heart with the right combination of words, the more they lash out. Their attack patterns will evolve, and require more and more skill to dodge the attack and keep yourself alive. Enemies hit hard in this game, and there’s no easy mode. Stray Children has no selectable difficulty option, and I believe the idea here was that how you choose to engage with Olders is essentially you picking the difficulty for every encounter. I love this, genuinely, even if sometimes I did want to toss my controller. If it gets me that heated, but still had me complete every boss with non-violent means, I think you’ve successfully made a good bullet hell game.

I think the real issue I have with this system is that it can be difficult to figure out the exact way to approach some enemies without extreme amounts of trial and error. You’ll find notes to give you hints on the molted husk of them you can find in the dungeon they appear in. Putting that information in the way the developers intended is pretty demanding. The hints on offer can be vague, straightforward, or frustratingly obtuse. Sometimes you’ll need to decode a simple number puzzle, or intuit that you have to repeat dialogue options a specific number of times. Mess up once in the sequence, and you have to restart. These only get more complicated as you go, and if you're trying to go full pacifist, you're in it for a really challenging game.

You receive experience however you decide to deal with a foe, but making the choice to play the game harder in exchange for a moral victory without violence has its benefits. You learn more about the kind of person the Older is, filling out your book with a last message they leave you to remember them by. Also, and this is important, they will be removed from the random battle pool. Pacifying all the Olders in a zone and then taking my time without random battles became my approach to every zone, and that was a great reward in and of itself.

While I have my frustrations with how battles play out, I think that this works with a game of Stray Children’s scale. There’s so much more to this game than just battles, with plenty of visually diverse locations to visit — all with charming aesthetic gimmicks. In those areas are unique puzzles and wonderfully charming dialogue from very odd characters, and I found these locations fascinating. There’s something very wrong going on in each of these places, as these children feel like cogs in different machines set up by the Olders that run the towns. The metaphor should not be lost on anyone, and the abrasive tone of the game’s commentary doesn’t need to sugarcoat anything.

This is where Stray Children’s heart lies. In a story about stagnating adults chewing up and spitting out children who just don’t know any better. It’s all filtered through this dream world you find yourself in, and it’s up to you to choose if these harmful people deserve to work through their problems or not. That trial-and-error nature of combat, as much as I think it was designed unevenly, does convey that dilemma throughout the entire game.

I hit credits after staying up really late one night, hours before I needed to be up the next morning for a long shift. The sleep I had after managing to finally beat it was unlike any I've had recently. Despite outlandish plot escalations (this is a good thing), where Stray Children ultimately landed was quiet introspection. It was sobering to say the least, and I fear that if any of the anxieties written into the Olders come from life experiences that the team should not be too hard on themselves.

Stray Children is basically everything I wanted from a successor to Moon. The friction I crave from that kind of game is here in full force, not even bothered with the idea that it might scare away any prospective players. The visual identity feels like it is building off that game, but it’s largely just doing its own thing. For every frustration I had, I found a new reason to respect Onion Games for doing it. With linear games like this, it’s very clear how almost everything here is a deliberate design choice.

What I get out of Stray Children, more than anything else, is that the people at Onion Games are some of the brightest creative voices in the business. There’s a subtextual plea in how this game was designed to understand them. Stray Children wants you to get the appeal of what used to make games like this so special, and that sincerity is infectious. I’ve seen so many retro revivals fail to understand why people liked games of the '90s. There was an excitement in partaking in the boom of a brand-new art form, and that excitement has understandably waned in the last 30 years. Stray Children takes that feeling and does something beautiful with it.